An appreciation blog for abstract art, in particular from the abstract expressionist school. Pollock, de Kooning, Hofmann, Frankenthaler, Riopelle, Gorky, et al. will be presented here. All rights reserved by the artists or their legal delegates.

Saturday, July 30, 2011

Friday, July 29, 2011

Thursday, July 28, 2011

Wednesday, July 27, 2011

Tuesday, July 26, 2011

Monday, July 25, 2011

Saturday, July 23, 2011

Friday, July 22, 2011

Thursday, July 21, 2011

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

Monday, July 18, 2011

Saturday, July 16, 2011

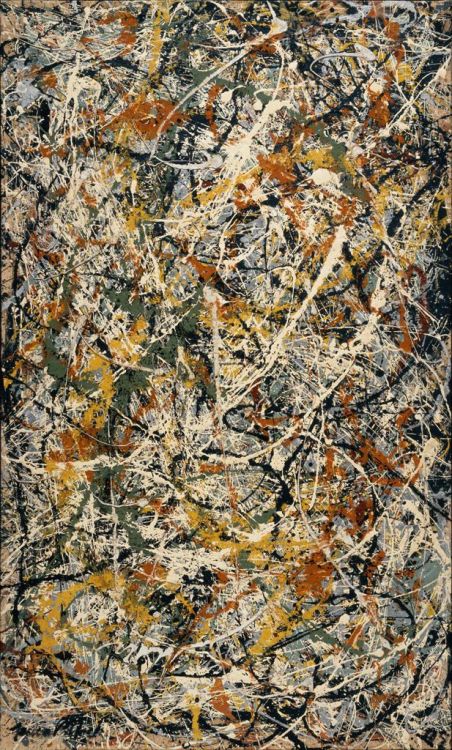

Jackson Pollock - Night Mist,1944-1945

From Jackson Pollock: An American Saga," the authors write the following:

With only a few months remaining before the scheduled March exhibition at Art of this Century, Jackson had virtually nothing to show. In the months immediately after finishing the Guggenheim mural, he had only produced a handful of exhibition-quality paintings, all of them in the same dense, rhythmic, abstract style. He had tried variations: sharp, jagged lines instead of great, flowing curves in The Night Dancer; smoky, turbulent browns instead of bright teal and turquoise in Night Ceremony. In Night Mist, he even stepped back across the line of abstraction toward fragmented imagery of Pasiphae.

Friday, July 15, 2011

Thursday, July 14, 2011

Wednesday, July 13, 2011

Tuesday, July 12, 2011

Monday, July 11, 2011

Saturday, July 9, 2011

Friday, July 8, 2011

Thursday, July 7, 2011

Wednesday, July 6, 2011

Tuesday, July 5, 2011

Jackson Pollock - Untitled, 1944

From Wikipedia: In attempts to fight his alcoholism, from 1938 through 1941 Pollock underwent Jungian psychotherapy with Dr. Joseph Henderson and later with Dr. Violet Staub de Laszlo in 1941-1942. Henderson made the decision to engage him through his art and had Pollock make drawings, which led to the appearance of many Jungian concepts in his paintings. Recently it has been hypothesized that Pollock might have had bipolar disorder.

Monday, July 4, 2011

Jackson Pollock - Untitled, ca. 1945

From Wikipedia: In October 1945 Pollock married American painter Lee Krasner, and in November they moved to what is now known as the Pollock-Krasner House and Studio at 830 Springs Fireplace Road, in Springs on Long Island, NY. Peggy Guggenheim lent them the down payment for the wood-frame house with a nearby barn that Pollock converted into a studio. There he perfected the technique of working with paint with which he became permanently identified.

Pollock described this use of household paints, instead of artist’s paints, as "a natural growth out of a need." He used hardened brushes, sticks, and even basting syringes as paint applicators. Pollock's technique of pouring and dripping paint is thought to be one of the origins of the term "action painting." With this technique, Pollock was able to achieve a more immediate means of creating art, the paint now literally flowing from his chosen tool onto the canvas. By defying the convention of painting on an upright surface, he added a new dimension by being able to view and apply paint to his canvases from all directions.

Saturday, July 2, 2011

Jackson Pollock - Guardians of the Secret, 1943

From theartstory.org: In its edition of August 8th, 1949, Life magazine ran a feature article about Jackson Pollock that bore this question in the headline: "Is he the greatest living painter in the United States?" Could a painter who flung paint at canvases with a stick, who poured and hurled it to create roiling vortexes of color and line, possibly be considered "great"? New York's critics certainly thought so, and Pollock's pre-eminence among the Abstract Expressionists has endured, cemented by the legend of his alcoholism and his early death. The famous 'drip paintings' that he began to produce in the late 1940s represent one of the most original bodies of work of the century. At times they could suggest the life-force in nature itself, at others they could evoke man's entrapment - in the body, in the anxious mind, and in the newly frightening modern world.

Friday, July 1, 2011

Ilse Getz - Cafe Dulciumi, 1959

From her New York Times obit:

Ilse Getz was a painter and collage artist who also made three-dimensional works, mostly with found objects. Ms. Getz, whose maiden name was Bechhold, was born in Nuremberg, Germany, and came to the United State...s in 1933 as a teen-ager fleeing Nazism. She studied at the Art Students League in New York.

The many exhibitions of her work over the years included shows at the Museum of Fine Arts in Phoenix in 1964, the Neuberger Museum in Purchase in 1978, the Kunsthalle in Nuremberg in 1978 and the Alex Rosenberg Gallery in Manhattan in 1981.

Stuart Preston, writing in The New York Times in 1959, described her oils in a show at the Bertha Schaefer Gallery on East 57th Street in Manhattan as "composed of a variety of 'incidents,' painted in alert fashion." He reported that "bouncing shapes leap vigorously about, covering the canvas with lively marks that make for general vitality."

Ms. Getz also designed the backdrop for the 1960 production of Ionesco's play "The Killer" at the Seven Arts Theater in Manhattan. The backdrop is now in the collection of the Hopkins Center at Dartmouth College.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)